To Reach the Top of a Mountain

Dreams Ahead is the title of Ann Cathrin November Høibo’s monumental, handwoven wall hanging, made especially for the Norwegian embassy in Washington, D.C.

Naturally gray wool forms the background of the abstract tapestry – a coarse, uneven surface that can be experienced almost as a gray wall, with large fields of unbleached white and charcoal gray pressing in from the sides, not unlike Norwegian skerries in springtime, when these small rocky islands are sprinkled with areas of snow that contrast with the dark rocks. Distributed across the tapestry’s surface are flashes of color: small, energetic drawings in bright orange and green, ice blue, pink, and pastel yellow.

The tapestry is without doubt the largest November Høibo has ever woven, measuring 216 in. high by 119 in. wide (5.5 x 3 m.). She made the work by hand all by herself, without any help from assistants – a quest that took her seven months of daily labor at the loom. The artist also had to rent a larger studio in order to produce on such a large scale, so she was given six-month access to a venerable gymnasium in the old city quarter of Posebyen, in Kristiansand, which provided a 3,660 sq. ft. (340 sq. m.) room to work in.

When we visit November Høibo in her temporary studio in February 2021, light is flooding through the high windows. As the artist says to us:

– This is a fantastic space to work in. Its dimensions change what it’s possible for me to make. I can produce bigger things here and work on several projects at the same time. The high ceiling gives me more headspace, I can walk around and move freely here.

Half of the space is occupied by another large project – two enormous stage curtains destined for Agder Prison. These are also 216 in. (5 m.) high each, and together are almost 4,000 in. (100 m.) wide. The stage curtains are being machine woven elsewhere on jacquard looms, in accordance with the artist’s instructions. And although they are not handmade, this project has helped the artist to understand how to work on large dimensions. In the other half of the studio stands the large warp-weighted loom on which November Høibo has finished about half of the handwoven tapestry that will be dispatched to the Washington, D.C. embassy. Initially, she had envisaged making two panels, each 60 in. (1.5 m.) wide – a little like the work created by Synnøve Anker Aurdal that hangs in a Stavanger bank built in the 1960s – but she is happy that this loom enabled her to create something more monumental in scale.

– I wanted to see if it was possible to weave the tapestry in one whole piece. This was a new challenge for me, and it gave the project a specific focus.

The loom that November Høibo is working on was built for the tapestry workshop A/S Norsk Billedvev in Oslo, which reproduced historic textiles for the Norwegian Museum of Decorative Arts and Design, and which was also employed in the 1950s to weave the enormous tapestries for Oslo City Hall. When the workshop closed in the 1970s, the loom was given to one of the handweavers. Today it belongs to her son, Per Hoelfeldt Lund. He runs a yarn-spinning business in Grimstad, from where November Høibo also purchases her spælsau yarn.

– I’ve been buying yarn from there for the last 10 years, and Per has shown me his loom from time to time. In their attic it took up the whole space and felt overwhelming, but here in the gymnasium it looks quite majestic.

Together with friends, November Høibo dismantled the loom and reinstalled it in her studio without any instructions.

– There were three of us and we moved the loom in a small van – the longest pieces sticking out of the boot. It was Astri Kvaale who also cut up all the yarn, and Morten Michalsen. He created a system using different-colored tape and labelled all the parts so that we would be able to reassemble the loom without further assistance. Apart from that, there’s been no practical instructions on how to operate the loom. I’m learning as I weave, and this is also a process I enjoy. At the same time, I’ve realized that all the different looms have basic things in common.

– What is fascinating about looms is how practical they are; they are actually not so complicated. It kind of reminds me of Norwegian coast life with boats and their rope systems, finding temporary solutions and making readjustments. Like in weaving, there’s a flow of rigging and practical details. What is special with this wooden loom is that we can walk into it and stand inside working on the warp threads and the metal weights that keeps them in place. It’s an old industrial loom, made so that the woven fabric can be inspected, to check the colors, and patterns, and so on. This loom with its giant size is reliable as a workhorse.

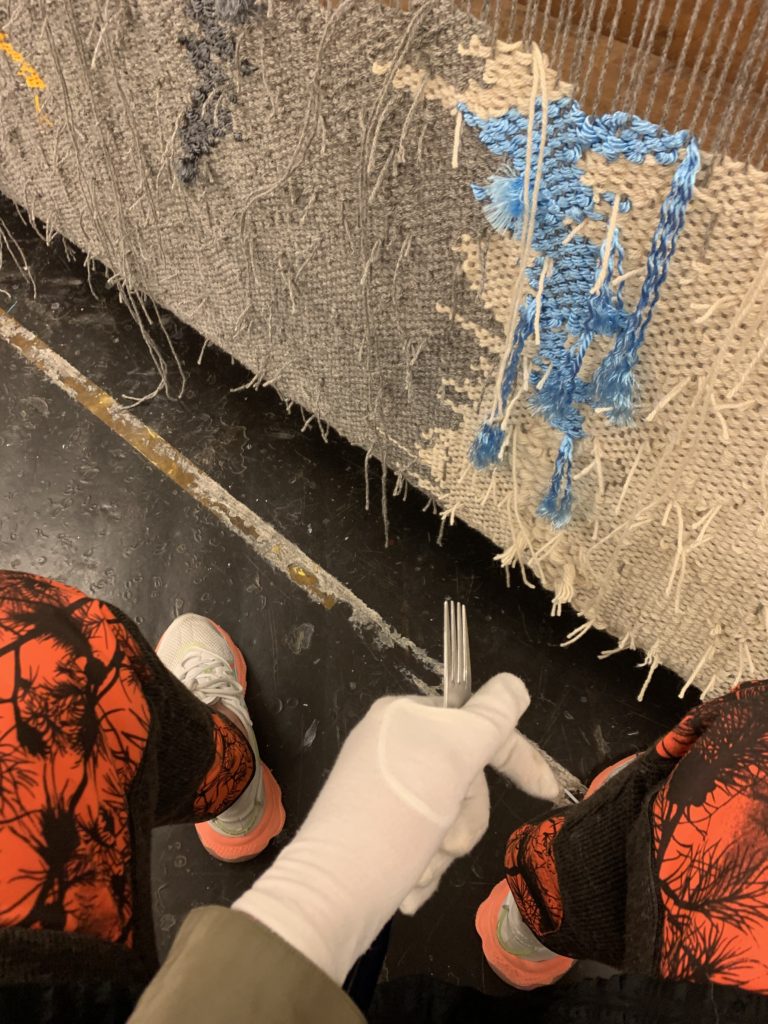

November Høibo weaves in an unconventional manner – sort of back to front – combining thick and thin yarns of various qualities and using only a fork as a tool.

– I use my own method: normally one looks at the front while weaving, but I have the backside of the tapestry facing me. From the beginning I wasn’t very interested in following any rules, so this method has evolved over the years, just by doing it. And I see that my skills have improved. For me, weaving is a lifetime project.

– I don’t follow the regularity in the weft, but concentrate on specific areas at a time. The weaving often grows as small hills or waves. Sometimes it also reminds me of playing Tetris: putting in threads where they’re needed so the whole fabric is connected. I get to think a lot while weaving, and I find it liberating to work so freely without a plan. Or rather, I have a “sense of a plan,” but it’s not stated expressly. Weaving is like life – you can make plans, but it doesn’t always turn out as you imagined.

– I use threads of different thicknesses and qualities. I touch the threads to feel them and get a sense of where they can fit best. The threads get locked into the weave and they settle down in a natural way. Intuitively I can leave an end of a thread on the front of the work. There’s nothing that is right or wrong, but I have to stay aware so that the thick threads won’t push the warp too much to one of the sides, and I keep the warp as straight as possible by controlling the evenness with the thinner threads. My tapestries will always end up a bit uneven and with intended irregularities.

– The thing with the fork is a technique I learned from Else Marie Jakobsen, who also wove like that. It’s a simple tool and easy to get hold of. I take whatever fork I can find. It’s just important that it’s not too heavy. Also, I need to have a lot of them, because I leave them all over the place. At lunchtime, the other people who have studios in this building can seldom find a fork.

November Høibo doesn’t make sketches as part of her process, but deems her previous works as preparations for her next one. When faced with the commission for Washington, however, she did attempt to sketch, but rapidly abandoned it.

– I wasn’t getting anywhere with the sketching, I just got stuck. So, I discarded them and went back to trusting my own way of working. It’s really enjoyable to understand that I can trust my own process and do what I know will work. I try to let go of fear and control, and to trust my own gut. This applies to all my choices, also of color. I love all colors, but not all color combinations. Sometimes I use combinations I really don’t like, because they can work surprisingly well in the composition. Like intense greens with orange and red, for example.

Usually, November Høibo buys her colorful yarns from a small shoe store in Madrid, bringing with her empty suitcases and filling them with rayon and cotton. This year, however, because of the coronavirus pandemic, she got some help from the Norwegian embassy in Madrid to buy the yarn for Dreams Ahead. In the studio, the big loom is surrounded by bundles of gray wool yarn, skeins, and pre-cut threads of colorful cotton – creating a semicircle of materials around her workstation.

– My surroundings are very important to me. It’s also important which colors are placed next to each other in the studio. One color can suddenly “pop” when it’s lying next to another color. I’m therefore not so keen on having colors hanging according to the color circle. When they hang more randomly, they suddenly glow a little differently.

Some of the colored yarn can already be found in the tapestry, even though November Høibo is using mostly gray wool. Making this slow work, she has plenty of time to weave in impressions from her surroundings, the seasons, and personal experiences.

– The tapestry takes in life. I respond to my environment – the seasons, the light, and my shifting moods. There are many emotions lying in these threads. Some days it’s incredibly good just to sit here and work, while other days it’s very lonely and frustrating and boring. It feels different to work on this after Christmas and after the U.S. election. It was quite draining in late autumn, when everything was dark, gloomy, and somehow very chaotic – it’s reflected in the dark colors at the top of the tapestry. Now the colors are brighter but cooler. We haven’t had this kind of white winter here for many years, with crisp snow, an unchanging blue sky, and a bracing breeze. The snow has made its way into the tapestry and it’s also possible to see the clear sky and colors. And soon it will get warmer …

Mountains and Landscape

The gray wool yarn used in both warp and weft came from the spælsau breed of sheep. It’s unusual to see such a valuable material used for the structural component of a tapestry. Traditionally, the warp is not visible – it is a supporting structure. In this work, the warp consists of 750 threads, meaning that 6,560 yd. (6,000 m.) of yarn were used for the warp alone.

– The reason that I began to make such good-looking warps was that I didn’t have the stamina to weave a full-length tapestry, so it was a strategy to exhibit the warps and make them a significant part of the works. The warp is as important as the weft. Ten years ago, producing this mountain of an artwork would have seemed completely unrealistic. But a year ago I made a tapestry consisting of four large pieces for an exhibition at [the gallery] STANDARD (OSLO). I then felt that I had gotten over a threshold, that I could cope with a kind of marathon – like this project. It’s not an option to give up, and I can’t wait to be liberated when I’m done.

To keep track of the many threads, November Høibo made them into braids when starting the tapestry.

– I don’t know yet if this will be the top or the bottom of the tapestry, and perhaps I’ll keep the braids when it’s finished. Many great characters have braids, and I’m also inspired by the ancient traditions of weaving in many cultures. There’s something very feminine and strong that I like about it.

Many great characters have braids, and I’m also inspired by the ancient traditions of weaving in many cultures. There’s something very feminine and strong that I like about it.

Photo: Kjartan Bjelland

She hesitates a little when we ask if she has any role models:

– If I have any role models? I am, of course, inspired by weavers, so it’s impossible not to mention Hannah Ryggen, due to her energy and attitude. It was really a bit because of her that I began to weave. I had a very physical reaction the first time I read about her in a women’s magazine in a dentist’s waiting room. The large tapestry by Miró that hangs in Barcelona made a big impact on me when I was very young and has possibly been a subconscious source of inspiration. But more and more, nature is becoming my biggest role model.

A warm gray and a darker charcoal gray, along with a large section in white, are the main colors in November Høibo’s tapestry at the embassy.

– When I think about it, there are a lot of rocks and stones in this tapestry – our gray mountains, quite simply. My only flight this year was to Stryn to visit the weaving mill that produced the digitally woven stage curtain for Agder Prison. I was reminded that the Norwegian landscape I flew over resembles the patterns and the colors of my tapestries. The mountain, and its cracks and fissures – its nerves in a way – and small lakes and snow. As we’ve talked about, I control things to some extent, but the pattern unfolds of its own accord. So this tapestry is definitely organic and very much linked to nature – a bit like how water finds its own course.

November Høibo was based in Oslo for a long time, and she has also lived in New York City for periods. Some years ago, however, she moved back to her hometown of Kristiansand, on the southern coast of Norway.

Has your art changed since you moved to a different landscape?

– Yes, I think so. Perhaps that is something that will show in my work, but over time. Like the difference between working in a small or large studio – it’s different living in a small or big city. Living here in Kristiansand changes my frame of reference, and living here does something to how I see the light and colors. This year, having been so slow, has also changed something. I’ve gotten interested in tiny details that I hadn’t seen properly before, because I didn’t have time to pay attention to them. Flower buds and structures in leaves, for example, or how birds get on with their work all day. It’s important to also think locally: one doesn’t necessarily need to travel so far. Since I haven’t gone anywhere for a long time, even Kristiansand has for brief moments felt like a big city. The buildings have become bigger.

While November Høibo has been working on this project, the world has been marked by the pandemic and lockdowns. With varying degrees of willingness, many people have had to reduce their levels of activity.

– It is quite an experience to stay home all the time. Before, I never really had time to unpack properly, and I always had the small (less than 100 ml.) shampoo bottles ready to take in my hand luggage. The last ten years have gone by in a flash, with nonstop travel and exhibitions. In February 2020, I had an exhibition titled “Hvis verden spør, så er svaret nei” (“If the World Asks, The Answer is No”), because I had planned to go into hibernation. I couldn’t bear the thought of boarding another flight, and then there were suddenly no flights to board. The world actually closed down.

– So, this project would have been complicated and stressful to make back in 2018 or 2019 for instance, as I would have multitasked more and would have needed more time to complete it. But now I can just concentrate on weaving. To get the opportunity to make such a tapestry, something really challenging, over time is fantastic. Now I’m working with a different focus. My tempo has slowed. I’ve also become more preoccupied with the actual weaving. Previously, I often combined sculptures and readymades with the weavings, but there’s less of that now. It could have something to do with age – as I get older my work develops. All factors play a part. All the time.

It’s not only the pandemic that has made November Høibo slow down her tempo. The loom itself has its own logic that she has to comply with.

This tapestry is so vast that it forces me to work in a different style. Previously, I worked more hectically, but these days I allow myself to use a whole day to roll up the tapestry onto the cloth beam, and to tie and untie all the knots for the weights one by one. And I tell myself that this is enough for today, so I keep my strength to continue again tomorrow. It’s a grown-up approach; it feels healthier.

– I’m in the studio every day, but I try to take some time off on Sundays. It gets cold to sit here for hours, and I try to have proper routines in order to persevere. I prioritize sleep, I walk to the studio to get warm, and I eat and hydrate properly. Once a week I have a yoga lesson with a tutor in the studio, which is appropriate since it’s a gymnasium. It’s about finding a balance. I have to be in good shape to work with handweaving. Actors understand this: they exercise regularly and eat well.

The titles of November Høibo’s works often refer to the artist’s own life – such as her solo exhibition “36,” in which all the works were given the title Untitled (36), and which took place in the year she celebrated her thirty-sixth birthday. Or the exhibition title “Hvis verden spør, så er svaret nei” (“If the World Asks, the Answer is No”) that we have already discussed. About the background for the work at the embassy – Dreams Ahead – November Høibo explains:

– I think it’s easier and more fun to work on projects if they have a working title. Dreams Ahead came to me immediately – also because this is a dream project. Everything felt pretty hopeless when the commission came: to weave a tapestry for a place with so much political turbulence, in the midst of an election campaign, and in the beginning of a pandemic. The title therefore came to be about long-term perspectives. The tapestry will hang in Washington, D.C. for a long time, and thus it’s about hope.

***

Ann Cathrin November Høibo was interviewed by KOROs Marte Danielsen Jølbo and Pernille Skar Nordby.

Var dette nyttig?

Takk for din tilbakemelding!

Takk for din tilbakemelding!

Vi leser alle henvendelser, men kan dessverre ikke svare deg.